There is a growing trend, particularly among younger individuals, to utilise AI chatbots like ChatGPT for emotional and psychological support. In fact, many users treat these systems as spaces for listening, comfort, and dialogue, sometimes preferring them to interactions with other humans, including professionals, precisely because chatbots avoid uncomfortable viewpoints, hold no personal history, and are not living presences.

This shift raises profound questions about the evolution of care practices, the changing role of experts, and our current need for meaningful relationships. What does it mean to seek the support of an algorithm today? And what does this reveal about how we construct the self and cope with suffering?

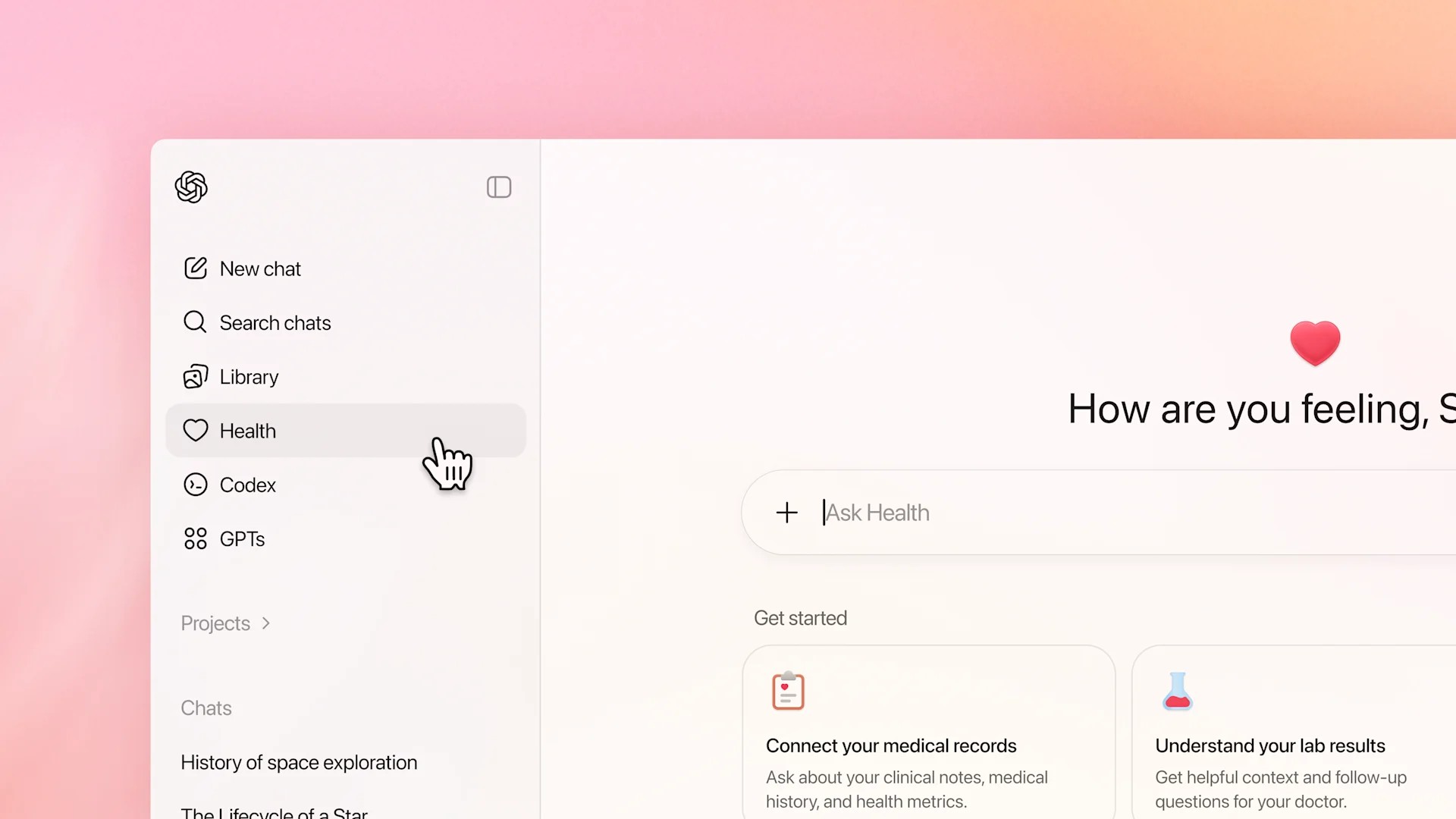

AI chatbots simulate aspects of human interaction: they answer promptly, never interrupt, and avoid judgment.

That frictionless, always-on presence makes them unusually approachable, especially for adolescents and young adults who may hesitate to share sensitive concerns with people in their lives. Yet it is essential to remember what these systems are: large language models (LLMs) that generate text by estimating the likelihood of word sequences. They do not “understand” your history, read nonverbal cues, or form a clinical picture of your needs. That distinction matters when conversations stray into mental-health territory.

Still, meaningful use cases are emerging at the margins of well-being. Students use chatbots to decode ambiguous messages or script calmer replies. Others treat them as “thinking partners” to defuse anger or clarify choices, not because the bot offers profound insight, but because the act of writing, receiving a structured reflection, and iterating promotes metacognition. In these contexts, the tool functions as a patient note-taker rather than a therapist.

Recently, a clinical psychologist, Harvey Lieberman, described using ChatGPT daily for a year as an “interactive diary.” He remained clear that it is a machine, yet found the practice helped order thoughts, interrupt rumination, and steady his inner monologue. At times, the model mirrored his reflective tone; at others, it produced flattering errors he corrected, reinforcing the need for human judgment. He concluded that while ChatGPT is not a therapist, it can feel “therapeutic” as a kind of cognitive prosthesis, scaffolding that supports understanding without replacing care.

This anecdote resonates with what many clinicians have observed: chatbots can help users express concerns and plan next steps, but they can’t guarantee attunement. This calibrated relational work underpins psychotherapy. Human clinicians listen to silence, rhythm, and posture; they question unhelpful frameworks and co-construct meaning over time. No text-based interface can replicate this.

So how should we think about responsible use?

1) Use chatbots as reflective surfaces, not diagnostic engines. Ask for options, rephrasing, and checklists, such as “List three alternative explanations,” “What are the pros and cons of waiting to answer?” Avoid seeking diagnoses, treatment plans, or prognoses.

2) Protect privacy. Abstract scenarios (e.g., “a close friend,” “a recent conflict”) and omit identifying details, medical specifics, or financial data.

3) Encourage balance. Invite the model to surface counterarguments, risks, and uncertainties. This reduces the likelihood of it reflecting your own biases.

4) Know when to hand off. If conversations touch on topics such as self-harm, acute distress, trauma, or complex medical decisions, seek qualified services. A chatbot can help you draft an email for a counsellor or prepare questions, but it’s not interested.

5) Develop digital health literacy. For educators, parents, and doctors, the goal is not to prohibit, but to guide use. Teaching how LLMs work, where they fail, and how to verify recommendations. Condemnation encourages clandestine use; literacy makes it safer.

There are also obvious pitfalls. Because chatbots aim to be helpful, they often provide answers even when it would be safer to use nuance, or “it depends.” They adapt to the user’s language and assumptions, meaning that a narrow or partial context can be reinforced rather than challenged; a fluent conversational style can be misinterpreted as authority. Consistency is not expertise; feigned empathy is not clinical empathy.

The balanced view is therefore simple. AI-powered chatbots can support organisation, motivation, and self-awareness by helping people express

concerns, simulate difficult conversations, and translate vague discomfort into concrete actions: scheduling an appointment, setting a boundary, and crafting a clearer message. Used improperly, they can amplify blind spots, offer plausible but superficial advice, and delay necessary human intervention. The difference lies in our expectations and habits: what we ask for, what we share, how we verify, and who we turn to when the stakes are high.

In short, as these tools become routine in daily life, let’s cultivate conscious and purposeful use, leveraging chatbots as companions for reflection while keeping humans (with their intuition, ethics, and care) at the centre of mental health conversations.

References:

Nadir Manna. Published on “Il Post” on 6 May 2025. Available at: https://www.ilpost.it/2025/05/06/chatgpt-psicologo-psicoterapia/

Harvei Lieberman. ©The New York Times 2025. Published on “La Repubblica” journal on 28 august 2025. Available at: https://www.repubblica.it/cultura/2025/08/28/news/intelligenza_artificiale_psicoanalisi_chatgpt_harvey_lieberman-424810821/